Interpeace is an international organization for peacebuilding. With over 25 years of experience, it has implemented a broad range of peacebuilding programmes in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, Europe, and Latin America.

Interpeace tailors its approach to each society and ensures that its work is locally designed and driven. Through local partners and its own local teams, it jointly develops peacebuilding programmes based on extensive consultation and research. Interpeace helps establish processes of change that promote sustainable peace, social cohesion, and resilience. The organization’s work is designed to connect and promote understanding between local communities, civil society, governments, and the international community.

Interpeace also assists the international community – especially the United Nations – to play a more effective role in peacebuilding, based on Interpeace’s expertise in field-based work at grassroots level. Interpeace achieves this primarily by contributing innovative thought leadership and fresh insights to contemporary peacebuilding policy. It also assists the international community through ‘peace responsiveness’ work, in which Interpeace provides advice and practical support to other international organizations (especially those in the security, development, and humanitarian aid sectors), enabling them to adapt their work systemically to simultaneously address conflict dynamics and strengthen peace dynamics.

Interpeace is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, and has offices around the world.

Putting local people at the heart of building peace

Peace cannot be imported from the outside. We believe that peace must be built from within societies. Together with our local partners, we create spaces for dialogue that allow for the active participation of local people to identify peacebuilding challenges and to develop their own solutions. By ensuring local ownership, we pave the way for the sustainability of peacebuilding efforts.

We ensure that priorities are determined locally and are not imposed from the outside. Local ownership ensures that local concerns are at the center of peacebuilding. If people participate in defining the problem, they have a sense of responsibility and ownership of the solutions.

Local ownership ensures that peacebuilding efforts are sustainable.

Trust is the keystone of peace

Trust holds relationships, societies, and economies together. Violent conflict dissolves it and that is why rebuilding trust is a core element of our approach. By working with all sectors and levels of society to develop a common vision for the future, we help to increase mutual understanding and restore trust.

Conflict tears apart the fabric of societies. Mistrust colours all relationships, including between people and their leaders. In such contexts, even small problems can escalate into wide-scale violence.

By providing safe spaces for dialogue, Interpeace helps societies to restore trust by identifying obstacles to lasting peace collaboratively and developing solutions to common problems.

Current policies often prioritise the ‘hardware’ of rebuilding countries after conflict: infrastructure, government buildings, demobilised soldiers, the timing of elections, police stations. Very often, these efforts fail to also focus on crucial ‘software’: reconciliation between former antagonists, trust in public institutions, and traditional practices of dispute resolution.

Trust gives institutions lasting legitimacy and helps individuals and groups to remain engaged in the long and arduous process of building lasting peace.

Building peace involves everyone

When key groups of society are excluded or marginalised, it sows the seeds of renewed violence. It deepens resentment and gives groups a reason to undermine peace. Our programmes are designed to include participants from across society – even those who are typically overlooked or seen as difficult to engage with. This inclusive approach ensures that a broad base of social groups shares ownership and responsibility for reconciliation and rebuilding their society.

Inclusion engages all parties in a process of change and begins to build bridges of understanding. In time, this enables the society to move collectively towards moderation and compromise.

Building peace requires a sustained effort

Building lasting peace is a long-term commitment. Transforming the way a society deals with conflict is a complicated process that cannot be achieved instantly. Our peacebuilding efforts take this into account and are designed as long‑term initiatives.

Building lasting peace takes time. The road to peace is bumpy, long, unpredictable and anything but straight. Support of local efforts must be patient and consistent.

External engagement must be predictable and must include long‑term financial commitments. Otherwise sustaining peacebuilding processes becomes impossible.

The Interpeace approach puts a focus on building trust. This approach to rebuilding society and institutions takes time and long-term commitment.

The process determines the result

We put a lot of effort into deciding what needs to be done to enable a society to build peace and just as much effort into how that work is done. It is vital to focus not only on the end goal of building peace, but on making sure that the process leading to peace is inclusive, is a process that builds consensus and encourages constructive dialogue rather than confrontation and power games. This is the only way to build sustainable peace.

Strengthening the foundations of a society that is divided is not business as usual. Mistrust tends to be deeply engrained. Major issues tend to be politically sensitive and urgent. Because of this urgency, the tendency is to propose technical solutions rather than to seek holistic solutions to complex problems. How the process is managed and how all sides carry out their engagements will largely determine the success of an initiative.

For peacebuilders, the global situation is worrying. Conflicts rage longer than ever – from five years on average in the past to 14 years today. Two-thirds of all humanitarian crises today are conflict-related. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is straining the United Nations-centred multilateral security architecture and is diverting attention from and changing the dynamics of other conflicts around the world, as well as having other far-reaching global consequences in disruptions to food, fuel, and finance. Political polarisation, discrimination, exclusion, and inequality are contributing to increased social tensions within countries in both the global North and South. These trends, exacerbated by the ongoing mutations of the COVID-19 pandemic, have eroded the shared commitment to commonly held norms and values while undermining trust in governments, institutions, and systems. Conflict and violence are the biggest obstacles to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, a deadline now less than eight years away.

If the current state of play worldwide is of deep concern, it need not define the future. In this crucial moment, all peacebuilders should be even more determined to foster trust and resilience, act creatively and assertively to strengthen multilateralism, and reinforce communication and positive linkages between national leaders and policymakers and the communities they represent and serve. In particular, the principles and operational models of peacebuilding must continue to evolve and improve. In particular, ‘resilience’ must be fostered as a comprehensive concept that equips individuals and communities to cope with adversity and also enables them to leverage and complement existing capacities in order to grow and gain in strength.

The traditional blueprint for achieving peace requires adaptation. Old and enduring questions call for new responses to address new imperatives.

In the global community of practice of peacemakers and peacebuilders, the bare minimum conditions of peace tend to be characterised as ‘negative peace’ – the absence of violent conflict and fear of violence. A broader, more sustainable and positive, and more forward-focussed concept is ‘positive peace’. This encompasses the attitudes, institutions, and norms that sustain societies in which conflict is resolved without violence. It requires transformed social relationships to address challenges of safety, justice, access to national resources and opportunities, well-being, and growth and development. Such a change from negative to positive peace cannot be achieved swiftly. However, Interpeace asserts that a deliberate foundational investment is required in building or rebuilding trust, strengthening social cohesion and resilience, and adopting inclusive and participatory approaches.

1. Trust is the bedrock of peaceful societies. It is fragile, quickly broken, and only regained through patient and persistent effort. Generating trust in the form of confidence, mutual respect, and understanding among individuals, and also between citizens and those who represent them, must be at the heart of any successful peacebuilding effort if it is to endure.

2. When analysing the causes of conflicts and designing solutions, the focus can often be on social divisions and obstacles to peace rather than on inherent and latent resources for peace. In doing so, opportunities can be missed to build on what is already working in society. When the conversation shifts from being about division to instead being about commonalities, then relationships can be strengthened and trust built. Enhancing people’s existing resilience for peace requires addressing sources of risk by fostering the diverse attributes, capacities, and resources that enable individuals, communities, institutions, and societies already potentially to deal peacefully with grievances in a non-violent way while also preventing new patterns of conflict and violence.

3. Local communities, civil society, and political elites often try individually to resolve problems and conflicts that must be addressed collectively if the solutions are to endure. Local processes can lack political buy-in, influence, and sustainability, and national policies can be seen as illegitimate or disconnected and so stymie implementation. External actors, too, can only foster meaningful change if their work is aligned with that of local and national stakeholders.

Local voices must be influential in shaping policies at national and international levels while, at the same time, leadership must engage citizens in the policy process. In so doing, citizens gain opportunities to speak and be heard, and gain experience of and contribute to governance processes that affect them. Civil society and local government or informal institutions play a bridging role and compress the distances between authorities and the people. Leaders recognise that their success and accountability are realised and enhanced by the depth of ownership of those most affected by national policies. Interpeace recognises the importance of this inclusive and ulti-layered approach to creating better quality peace, and it is reflected in its ‘Track 6’ methodology, through which peacebuilding efforts are advanced with actors at Tracks 3, 2 and 1 in a mutually supporting and integrated way.

The international community, and the multilateral security system especially, offer the framework and opportunities to create and sustain peace, especially since many of today’s violent conflicts almost inevitably involve international actors beyond the parties immediately in conflict.

However, even though the nature of conflict has fundamentally changed with more occurring today within rather than across sovereign and state borders , international approaches to peace have remained the same since the UN framework was established after the inter-state Second World War of the mid-20th Century. Too many peace processes have since failed to reduce or end violent conflicts effectively, let alone build lasting peace. Meanwhile, whilst the Geneva Conventions outline the rules of engagement during times of war, a set of complementary norms does not exist to guide if not govern how to build peace in this constantly evolving conflict landscape.

Several years ago, Interpeace proposes and started to incubate a globally inclusive effort to draft a new set of globally acceptable and practical Principles for Peace. Interpeace has since hosted an international commission and secretariat, which have consulted widely and inclusively on the draft Principles in a process that has no single owner or sponsor but draws in all possible peace actors, including grassroots communities, governments, and regional actors. The Principles are intended to be new foundations for peacemaking and peacebuilding, anchored by the United Nations Charter and UN system, agreed by all, and therefore legitimate in the eyes of all stakeholders. Based on extensive research and learning as well as consultation, the Principles will be launched at the end of 2022 and are expected to be supported by capacity-building and transparency initiatives that will show how and where the Principles have been applied, with what success.

Dealing with the realities of conflict and violence is not the exclusive terrain of peacebuilding organisations. It is also a critical factor with profound consequences for all development and humanitarian action. For this reason, development and humanitarian actors operating in conflict-affected contexts need to continue to enhance their ability to contribute deliberately to sustaining peace through their more sector-specific programming. Interpeace is building practical bridges in the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus through its work on Peace Responsiveness. This takes the international community beyond the silos in which most operate, away from the conventional and relatively passive model of considering ‘conflict sensitivity’ towards a more holistic, practical and, enduring approach to technical interventions which concurrently contribute to peacebuilding outcomes.

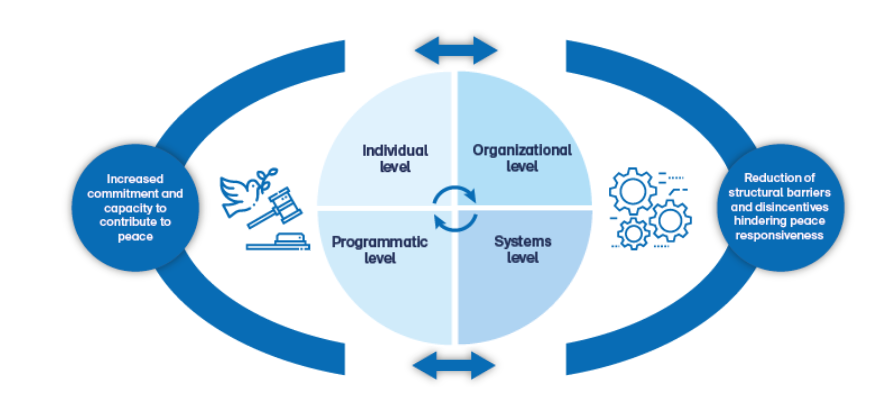

Peace Responsiveness work has continued to multiply, focussing initially on the development sector and now extending into the humanitarian. In each case, Interpeace works at four levels which (1) contribute to systemic change, so that the quality of humanitarian, development, and peace work is improved in a sustained way; (2) contribute to organisational change, so that each actor hardwires the changes required into its own policies and procedures, and owns them by choice; (3) contribute to changes in the perspectives and behaviours of key individuals in each of these sectors, building their capacities to be change agents of strengthened technical and more peace-oriented interventions; and (4) contribute to systemic, policy, and behavioural change with practical shifts at the community level, by building peace responsive methodology into in-country programming.

The roots of many conflicts can be traced to some form of social, political, or economic exclusion. Paradoxically, solutions themselves also tend to be exclusive. International stabilisation missions, for example, have become an important part of the international toolbox in conflict-affected areas. They are mandated to improve the stability and peace of communities that are experiencing active armed conflict. However, they also tend to be limited in their effectiveness, owing to compromises between competing external actors and rivalry among in-country elites. Other dilemmas include the imperative to act swiftly to stop bloodshed, and the difficulty of leaving contexts where security and the rule of law are weak. And even where stabilisation missions have endured many years, they still tend to be based on short-term planning horizons.

For Interpeace, all peacebuilding, including stabilisation, is ultimately a process towards achieving sustainable peace and development for the benefit of individuals, communities, and the governments that serve them. Clarity on this ultimate goal is essential, especially when international actors are involved, in order to define and recognise for whom peace is intended.

If this report’s ‘In Focus’ reflects increased stress and conflict globally in 2021, it was also another year in which Interpeace remained dedicated to thinking innovatively and to delivering practically in ways that both demonstrate and achieve the potential of peacebuilding. And 2021 was also a reminder that peacebuilding, to be effective, must retain a methodology and a mindset that is anchored in inclusion, participation, persistence, adaptability, and human dignity.

Although the peacebuilding sector has recorded significant achievements in the last decade, it needs to reassess and adjust the parameters it uses to design, implement and monitor peace processes. It also needs a framework for assessing whether security, development and peacebuilding efforts in conflict-affected countries truly contribute to resilience for peace; and to use the evidence it generates to shape better actions. At the same time, funding for peacebuilding is currently limited and continues to be delivered in short-term increments: as a result, it is misaligned with medium and long-term peacebuilding processes and with the scale of need. Innovative financing solutions will be required to incentivise the private and public sectors to work together to leverage their resources for change.

Interpeace has developed a Trust, Resilience and Inclusion Barometer, which will be piloted in Ethiopia in 2022.

0

A new framework for peace

|

Practitioners, researchers, and policymakers have long recognised that the international community's approach to contemporary peace and conflict challenges has significant limitations.

Principles for Peace is a collective and participatory global initiative to develop a new set of principles to support national and international actors in crafting more effective and inclusive approaches to peace.

The initiative is spearheaded by an International Commission on Inclusive Peace and an independent Secretariat incubated and hosted at Interpeace. The initiative is supported by over 120 organisations and a Ministerial level Steering Committee, forming an influential coalition of actors advocating for a new approach and agenda for peace.

A new set of principles to reshape peace processes

The P4P initiative has gathered momentum and has increasing support. The network of UN Member States and organizations that are involved in different lines of engagement has grown steadily. The principles are anchored in a broad process of consultations, evidence-based fact finding, sustained engagement with high-level decision-makers, and input from over 60 countries. The process has thus far benefitted from gathering over 100,000 insights to-date.

0

Finance for Peace

|

Interpeace’s Finance for Peace initiative is based on two priorities in Interpeace’s five-year Strategy: the initiative spearheads Interpeace’s work to change the way peacebuilding is financed; and it is a pillar of Interpeace’s work to integrate economic outcomes in peacebuilding action. Since its inception, Interpeace has involved a range of finance sector, development finance institutions (DFIs) and other organizations in the development of innovative financing approaches to peace, in parallel with environmental, social and governance (ESG) and SDG investing approaches related to peace.

This initiative responds to one of the fundamental challenges facing conflict-affected and fragile societies: their inability to attract private investment and grow in ways that are equitable and sustainable. Private financial flows to conflict-affected and fragile States should be the bedrock of sustainable economic growth, yet have consistently fallen in the last 10 years. In the wake of Covid-19, current foreign direct investment (FDI) to fragile and conflict-affected places is currently three times lower than the previous 15-year average. This underscores how important it is to rebuild private investment in the world’s fragile places. Meanwhile, Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) is under constant challenge and peacebuilding financing from traditional donors has been stagnating. Peacebuilding can play a vital role in rebuilding private sector investment, because it reduces the risks that often deter private investors from engaging in fragile settings. Finding new ways to enable the finance and development/peace sectors to cooperate is critical to addressing this challenge.

By means of a multi-sectoral process and wide consultation across different sectors, Interpeace has developed a feasibility report that outlines a new approach to increasing finance for peacebuilding. The adoption of Peace Bonds, guided by an international normative framework, would offer specific incentives for private investment to support peacebuilding outcomes.

In 2021, with support from the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), Interpeace established the feasibility of peace bond structures. Its analysis describes the key financial mechanisms, standards and practical partnerships that would be required and shows that peace bonds could generate a win-win-win outcome for investors, communities and governments. The research demonstrates that investors who integrate peace actions in development projects can produce a more profitable outcome for themselves as well as material benefits for communities.

Interpeace has also been working with a number of governments who will champion innovative finance reforms and the Finance for Peace agenda at key future events, such as the 2022 UN high level summit on financing and the 2022 G7 meetings in Berlin. Interpeace generated sector-wide momentum by presenting these new financing approaches at the 2021 Building Bridges Summit in Geneva.

Bridging the gap between the cessation of violence and longer term stability

In the last 20 years, international stabilisation missions have become a major part of the international intervention toolbox in conflict-affected settings. Mandated to improve the stability and peace of communities experiencing armed conflict, their stated purpose is to reduce violence and lay foundations for longer term security. In practice, however, they have often failed to meet their stated goals, and in many instances have even contributed to local conflict dynamics. Faced by this experience, local populations have raised questions about which interests are prioritised, and whether such operations, as they are currently designed, ultimately enable local and national actors to manage their security challenges.

To address these issues, Interpeace is leading a two-year initiative, called Rethinking Stability, in partnership with the German Federal Foreign Office (GFFO), the Bundesakademie für Sicherheitspolitik (BAKS), and the Atlantic Council. Through a series of frank local, national and international dialogues, bilateral meetings, and original research papers, the programme revisits and questions the conceptual and operational assumptions and approaches behind stabilisation efforts, with the aim of improving the effectiveness of future efforts to promote lasting peace for the communities they serve.

In 2021, Interpeace held dialogues in Washington D.C. and Bamako, met with leading experts and organizations working on stabilisation, and developed several papers on key issues (challenges facing the field, lessons the initiative has learned, and original research on the stabilisation programme in Mali). The initiative has taken an inclusive approach: the Bamako conference on People’s Perspectives on Stabilisation was an opportunity to bring community-level concerns into high-level policy discussions. As a result, it was recognised by all relevant actors (INGOs, think tanks, and government-affiliated bodies) that Interpeace’s initiative is posing the right questions at a time when introspection and review are needed. Although the Mali report (‘Examining International Stabilisation Efforts in Mali’, EISEM) has not yet been published, its findings have been validated by MINUSMA, the GFFO, FCDO, the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs/Department of Peace Operations (DPPA/DPO) West Africa division, and academics.

Resilience for Peace is central to the ability of communities to manage their divisions and tensions legitimately, inclusively and non-violently. Peacebuilding at community level could be more impactful if it harnessed, organized and supported the energy and commitment of local people to make their own communities more cohesive and prosperous. At the same time, Interpeace does not invest its efforts solely at community level, but also seeks to enhance transformative resilience in institutions at national level, giving special attention to the relationship between national security services and citizens.

Overcoming the barriers to inclusion that prevent youth and women from participating fully in society and making their own contributions to peace is a second important focus. Long overlooked, inclusive economic and development solutions to buttress peacebuilding efforts are progressively being integrated into our work. Similarly, Interpeace programmes and policies are giving more attention to the central importance of justice and human rights in the pursuit of lasting peace.

2 community development plans with the private sector

Supported 148 local infrastructures for peace in 10 country programmes.

805 local initiatives that contributes to the transformation of 162 local conflicts

3 formal state-level partnership agreements (DRC, Burkina Faso and Rwanda)

Interpeace launched 2 new country programmes in 2021: Yemen and Ethiopia

18 projects specifically focused on promoting Youth, Peace and Security.

7 partnerships for human rights and peacebuilding work

12 programmes integrating peacebuilding and development

6 security reform initiatives

Women, key local change agents

The deep political divisions that characterise Libya stem from and feed into local grievances, creating a negative cycle. Exhausted by the prolonged state of conflict, Libyans are frustrated with continued political stagnation, failed dialogue processes, and unkept promises. Years of conflict have also weakened already fragile social cohesion and widened social and economic gaps in the country.

In this highly divided context, community-based reconciliation processes are critical to addressing conflicts stemming from local grievances. Often, however, local populations and communities are not sufficiently involved in higher-level peace processes. To bridge this gap and in line with its Track 6 approach, Interpeace has gathered together and fostered for the last decade a broad range of “change agents” to establish and promote a common vision of priorities for peace and to find local solutions through community dialogue.

The added value of local peace and reconciliation processes

Through its project Strengthening Local Cohesion in Libya: A Pathway to Lasting Peace, Interpeace seeks to reinforce local resilience capacities for sustainable peace and help develop a local environment that is conducive to stability and future growth in Libya.

In the last 10 years, Interpeace’s programme in Libya has developed and accompanied a network of over 200 change agents or “dialogue facilitators”, who work directly with the population in all parts of the country. Change agents play an important role in building resilient peace in Libya by ensuring that communities are equipped to be more resilient to conflict.

Women play a critical role in resolving conflict in Libya

Mediation within and between communities is usually reserved to men, especially elders, whose undisputed authority makes them guardians of tribal custom and the final authority on most community matters. Women’s rights and opinions are often ignored and are under-represented. However, when women become more involved in conflict transformation, more avenues are open for understanding different positions and identifying underlying causes. Interpeace’s work has demonstrated that women are often able to find ways to open dialogue between conflicting parties and help them find solutions.

Gender integration and women’s empowerment are vital to the advancement of peace, social cohesion and long term stability in Libya. For this reason, women change agents play a central role in the project’s strategy to build intra-communal cohesion and strengthen links and networks within and between communities.

From the start of its work in Libya, Interpeace has endeavoured to include women as key actors of change, despite the conservative nature of Libyan culture. Women are crucial connectors at community level and have enabled the programme to address culturally sensitive questions on women’s issues.

“On the practical level, I was greatly empowered in my social participation. There were some activities I stayed away from, thinking they belong to the specialists, and I never participated. I felt that it [the initiative] gave me the courage to participate. I was staying away from those having opposing ideas and positions, but I began to intervene in positive ways. If a tough situation occurs, I try and find constructive solutions to it,” said a female change agent from Tobruk.

Youth leadership at the core of mechanisms to defuse tensions

Interpeace’s engagement in Burundi has been driven by a long term peacebuilding strategy implemented with its partner, the Conflict Alert and Prevention Centre (CENAP); its reach and scope have recently expanded to include four additional partners. A key goal of the programme has been to strengthen the resilience capacities for peace of youth and to promote inclusive decision-making in pursuit of a common vision. This is especially critical in a context where 64% of the population is under 24 years old and can be vulnerable to negative political influences.

The Buhumuza campus, a branch of the University of Burundi, is located in an area that borders Tanzania (Cankuzo). The area is at permanent risk of upsurges of inter-ethnic tensions due to repatriation of many refugees from Burundi’s political crisis in 2015. In this newly established campus, which opened in 2020, there was no space for exchange between members of these communities. “The Buhumuza campus was often subject to political and ethnic tensions,” testified the campus manager. Students also reported that they used to lack an established way to deal with conflicts.

In the framework of Interpeace’s Building Synergies for Peace Project, implemented in partnership with five organizations, on 12 March 2021 CENAP and Jimbere magazine organized and facilitated a debate on the Buhumuza Campus on inter-ethnic marriage and peaceful cohabitation. The student community made a number of recommendations for gradually resolving the problem of ethnic cleavages. One was to develop economic activities to enhance social cohesion and reconciliation. After this debate, a significant number of students said that the exchanges facilitated and presented by Jimbere magazine and CENAP had opened their eyes to the importance of income-generating activities as a unifying mechanism. As a result, the students took the administrative steps necessary to set up a cafeteria cooperative, run by the students themselves, which opened in September 2021.

This cafeteria provides a critical space for the students to share work experience, discuss different economic activities, help each other, and collaborate to consolidate cohesion and establish bonds of solidarity. "These activities have helped us in our cohesion by erasing potential ethnic discriminations. We collaborate beyond the cafeteria, and this strengthens cohesion and attachment beyond our different ethnicities," .

In order to make the cooperative a unifying mechanism, the students set up a supervisory board. After its establishment, the university administration reported only one case of ethnic conflict, which was resolved by the supervisory board itself.

Improving conflict prevention and local security governance in the Sahel, Boucle du Mouhoun, and East and Centre-North Regions of Burkina Faso

In recent years, Burkina Faso has experienced a dramatic increase in intra and inter-community conflicts, which are sometimes violent and in many regions exacerbated by the emergence or resurgence of self-defence groups. This has led to and continues to cause large-scale population displacements throughout the country.

Intra- and inter-community tensions are fuelled in addition by a general lack of awareness of the roles of the armed forces of Burkina Faso and their responsibility to maintain peace, and by the low involvement of women and youth in security governance. To ensure lasting and sustainable peace, it is vital to continue to improve civil-military relations as well as security governance, and to strengthen community engagement in conflict prevention and resolution.

Interpeace is working with the National Ministries of Security and Defence, the National Institute of Statistics and Demography (INSD), the Centre for Sustainable Peace and Democratic Development (SeeD), Indigo, the Peacekeeping School, and Women in Law and Development in Africa (WILDAF), to strengthen and integrate peacebuilding approaches in security governance in the Sahel, Boucle du Mouhoun, and East and Centre-North Regions of Burkina Faso.

The ultimate aim of the project is to promote peacebuilding approaches in security governance in these regions, as well as inclusive, participatory and collective security management, by improving relations between traditional security actors and communities.

Since the official launch of the project in 2021, Interpeace and its partners have mapped security sector actors in the different regions, conducted satisfaction surveys on security service provision, and held regional consultations and workshops with identified stakeholders to understand current security dynamics in the regions.

These consultations have assisted populations to understand current conflict dynamics through their contact with security actors, and also their own roles in building social cohesion and sustainable peace in their communities. “It is the first time I have been consulted on security issues, and I think it is a good thing to be given the opportunity to express myself on such an important subject,” said one stakeholder, who affirmed that combating insecurity is everyone’s concern and responsibility.

Though still in its infancy, the project has generated a detailed, shared description of the security dynamics of the four target regions, and insights into the roles of women and youth in local security. The active participation of the Ministries of Security and Defence has demonstrated that the national government is willing to rethink local security sector governance and find more peace responsive and participatory paths to lasting peace.

Baseline perceptions of safety and trust towards security actors in Burkina Faso

Sustaining peace through locally led peace infrastructures

For decades, conflict has been an everyday hardship for the nomadic communities of Kenya’s North Rift Region. Social, cultural, environmental, and political factors drive cyclical violence that has shaped antagonistic inter-group relations, spreading fear and mistrust.

The valley of Suguta, known as the “valley of death”, had become synonymous with violence, grieving, and loss caused by cattle raids, pillage, and massacres. As violence spiralled between the Turkana and Samburu communities, local police recorded an average of six deaths and three livestock raids every month prior to 2021.

The aim of Interpeace’s engagement in Kenya is to set up sustained capacities for conflict transformation. Interpeace works with its partner, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC), to foster cross-clan collaboration, reconciliation, mediation, and dialogue between communities, using insider mediators and inclusive dialogue processes. Building on their previous engagement in Kenya’s Mandera County, Interpeace and the NCIC are replicating a successfully piloted Ceasefire Monitoring Committee (CMC) model in the North Rift Region. CMCs are locally owned community peace infrastructures that can sustainably transform societal conflict.

In July 2021, the programme successfully brokered a truce between the Pokot and Turkana communities, which have been fighting for the last 65 years. After a comprehensive and inclusive consultative process, Interpeace and NCIC convened Turkana and Pokot elders who gathered at the town of Orwa, in the border zone between Pokot and Turkana territories. Through a dialogue facilitated by Interpeace with the NCIC, the elders agreed to a ceasefire and nominated four of their most trusted counterparts to become members of a CMC.

CMCs create the conditions to transform conflict. They seek to identify and mitigate the key triggers of fear and mistrust that create inter-community hostility. In addition, members of the CMCs work with communities to disarm local militias, ensure that displaced persons return home, initiate and facilitate dialogue, and enhance social cohesion. The CMCs work to restore trust, nurture a culture of peace and reconciliation, and address structural issues that often trigger conflict in the communities.

The signing of the Orwa Peace Accord in July 2021, which put an end to decades of cyclical conflict and deadly violence, was possible due to the willingness and commitment of communities to share a new future together.

“For 85 years I have run across the Suguta Valley organizing raids or recovering my raided livestock, but the last two years of my involvement in peace have shown me a life beyond this valley. I have travelled to Nakuru, Nairobi, and Mandera, learning how to live with other people. My two years of peace are worth much more than my 85 years of living in conflict,” said a member of the CMC.

The Suguta Valley is now telling a new story about itself, a story of positive change, and it is no longer known as the “valley of death” but “the valley of peace”.

Inclusion of women generates a more effective peace process

After five years of conflict between the State and pro-independence Tuareg and armed groups in northern Mali, a peace agreement was signed in 2015. The Algiers Accord includes a DDR programme, designed to enable ex-fighters to end hostilities and reintegrate into society. It enables ex-rebels to join a unified Malian army or follow civilian vocational training to obtain sustainable livelihoods.

Some challenges have arisen that have impeded the peace agreement’s implementation. Lack of enthusiasm for an integrated army by some high-level stakeholders and soldiers, as well as changing conflict landscapes, lack of resources, and the global pandemic, have significantly delayed its implementation. Interested members of the parties in conflict (independentists, armed groups, but also self-defence militias who have taken up arms more recently) are disappointed and angered by these delays, as well as by a failure to inform citizens about the nature and progress of the DDR programme.

In this context, Interpeace and its partner, the Institut Malien de Recherche Action pour la Paix (IMRAP), have designed a programme to facilitate implementation of the DDR programme, and support State institutions at all levels to inform the public about the process and its conditions.

Specifically, the project identified a substantial information gap among women in communities particularly affected by conflict. Because they were not seen as parties to the conflict, they were not included in efforts to explain the peace agreement – in fact, some women interviewed did not know one existed. Women in these communities generally do not understand the DDR process or its potential to make their families safer, and many do not believe it will be implemented effectively. This was identified as a missed opportunity, because the importance of the role of women in these communities cannot be overstated. They have the power to raise awareness in their communities, particularly among male fighters, and can encourage them to drop their weapons and join the DDR process.

In the centre of Mali, in the Region of Mopti especially, a fragmented conflict landscape has led to the emergence of autochthonous armed fundamentalist movements as well as self-defence militias organized on ethnic lines. DDR structures are stigmatised by women in Mopti, because they are seen to benefit young people from other conflict areas at the expense of their own young men. Interpeace and IMRAP therefore asked women from the Mopti villages of Socoura and Fatogoma to participate in joint discussion sessions with local DDR Commission officials, where their concerns were raised and discussed.

As a result, they understood better the purpose and conditions of the DDR programme and became interested in sensitising communities around them. Local Commission members realised the potential of involving women in their efforts and expressed their desire to work together with the women on an inclusive awareness-raising campaign to recover weapons and reintegrate ex-fighters. They started the process by discussing the issues with 30 women from four women's associations, as well as youth, with support from Interpeace and IMRAP. Over time, this campaign by women’s associations and the DDR Commission persuaded members of local self-defence militias to support the DDR programme.

This success is remarkable, because civil society actors, ex-fighters, and DDR authorities all came together to work for DDR. At the same time, it remained very sensitive to engage armed actors on issues of demobilisation in an area of active conflict. To navigate this challenge, the Interpeace team always involves local authorities from an early stage to obtain information on volatile security conditions. In this case, some of the initial sessions were held very discreetly in order to establish community acceptance.

Strengthening dialogue and collaboration between citizens and authorities in Ituri Province

Violent confrontations in the Ituri Province of the DRC have killed, wounded, and displaced many people. Arbitrary arrests by the military fuelled frustration within communities and complicated collaboration between the security forces and the population. Furthermore, violence between the security forces and several youth militias created mistrust of all young people in the region.

Interpeace's programme in Ituri Province seeks to improve community safety by promoting dialogue and collaboration between citizens and the authorities. The programme established Permanent Dialogue Groups (GDPs), key spaces in which all stakeholders are able to discuss and co-design solutions to conflicts.

In Nyankunde, Irumu territory, the efforts of the local GDP and the authorities significantly lowered tensions between the security forces and youth. Supported by the local authorities, the Nyankunde GDP organized a series of reconciliation dialogues between the security forces and young people. These helped young people to understand the security forces' work and helped the security forces to recognise biases in their behaviour towards young people, demonstrating to both that peaceful resolution of tension was possible. As the Commander of the Congolese National Police in Komanda explained, the dialogue fostered mutual trust in a complex situation. He added that most people want "peace and not conflict because they know the consequences of war".

In February 2021, the GDP of Nyankunde, in collaboration with the administrator of Irumu territory and leaders of both communities, supported community barzas (dialogues) between Bira (most of whom are farmers) and Hema (most of whom are herders). The barzas, which were preceded by a consultation process led by the GDP, discussed peaceful solutions that would resolve tensions between the two communities. Recent population growth, and the different demands of their livelihoods, had increased competition over land. Destruction of Bira farmers' crops by Hema cattle added to these tensions. Facilitated by the GDP’s mediation, the two communities agreed to find solutions through conciliation. The barzas also presented an opportunity to sensitise the communities on issues such as gender-based violence and land conflict. Both the dialogues and awareness-raising were effective, in that the communities no longer hesitate to request GDP mediation to resolve conflicts. This underlines the key role that GDPs play in transforming conflict dynamics in a sustainable manner.

Healing the wounds of genocide and fostering resilient communities

The impact of the genocide against the Tutsi still weighs heavily on Rwandan society today. The country continues to grapple with a burden of trauma and mental health problems. The release of some perpetrators of the genocide, on completion of their prison terms, has made the situation even more difficult. Reintegration is often an extremely challenging experience, both for the former perpetrators and the communities that receive them. The concerns that released ex-prisoners report most frequently are social stigma, rejection by their family, and inability to find a livelihood.

Building on its longstanding engagement in the country, Interpeace launched an innovative and holistic trauma-healing programme in Rwanda, to expand investment in mental health, address trauma, and enhance social cohesion. Operated in partnership with two key partners – the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission (NURC) and Prison Fellowship Rwanda – this programme is contributing to Rwanda's efforts to address its people’s invisible but deeply-felt wounds, and complement the investment and progress already made by the government and local civil society organizations to heal trauma and improve social cohesion and livelihoods.

"My father was jailed for being accused of committing genocide. He later died in prison. I was deeply wounded because I was the one who reported where my father was to those who took him the day he was arrested. The one who arrested him was my neighbour. I got angry at him, and I used to say that I would never forgive him, because my father was imprisoned and died there. However, after listening to the testimonies of genocide survivors who forgave those who exterminated their relatives, I also forgave my neighbour, and through their testimonies I understood the reason why my father was imprisoned," said a young descendant of a genocide perpetrator, in the Kamabuye sector, Bugesera.

To date, 480 people, including genocide survivors, ex-perpetrators, and their descendants, have graduated from the socio-therapy programme. Change stories collected from them indicate that individual healing from trauma and anxiety has improved, and trust has increased, creating the basis for forgiveness and reconciliation, as well as cooperation in livelihood activities.

In the process, Interpeace's programme has worked with community facilitators, different local authorities, and other local actors who support healing groups. They particularly helped the project to identify potential beneficiaries.

Transforming perceptions of youth and community safety

Youth in Côte d'Ivoire are often perceived to be drivers of political violence. To combat this misperception, Interpeace and its partner Indigo Côte d'Ivoire implemented YPS in Practice, which aims to enable the country's youth to participate as actors and leaders in peacebuilding initiatives.

Funded by the United Nations Peacebuilding Fund (UN PBF), YPS in Practice identified 40 young leaders from seven community initiatives already active in their neighbourhoods in Yopougon and Abobo. The project trained and accompanied them in the design and implementation of projects to build peace and prevent political violence. The project targeted young people under the age of 35. Half were women, and half were under 25 years of age.

The young leaders were asked to make their actions more inclusive and participatory by engaging stakeholders from a range of backgrounds, including youth under 25 and women. This objective was achieved because youth-led community actions now run inclusive and participatory analyses of the problems they seek to solve, using participatory action research (PAR) tools.

Ms. K., who leads a women's association working for social cohesion, had negative perceptions of young people in her neighbourhood, believing they were involved in the criminal economy. In 2021, the project brought together actors from all sectors of society, including young people, and she had the opportunity to discuss with them the neighbourhood's insecurity and her own experience as a victim of theft. The dialogue made her aware of the problematic social context that pushes young people to violence. Today, she sees them on a daily basis and has become a positive influence on them. Empowered, valued, and understood, they have made a specific, enduring commitment to contribute to peace in their neighbourhood and reduce acts of violence.

"Today, everyone's opinion is taken into account, even those under 25. Before, it was the leader alone who decided on the activities and who managed the finances," said Abdoulaye Coulibaly, member of Conscious Generation Côte d'Ivoire.

"Thanks to PAR, we have included ex-combatants, young people from smokehouses [places of drug consumption], transporters, and traders in our activities. We understood through the discussion groups that each world has its own perception of violence and also the different reasons that push young people to engage in violence," said Alassane Coulibaly, member of Conscious Generation Côte d'Ivoire.

The project has enabled young leaders to adopt and promote inclusive approaches in their social and even professional life, contributing to a more inclusive society through their actions.

However, a few challenges still need to be addressed. In Côte d'Ivoire, "you are young until you are 40", and gerontocratic dynamics prevent those under 25 in particular from taking an interest in certain subjects or being recognised by their elders for their skills or interest in peace and security issues. One of the programme’s strategies is to show teams and project participants why it is important to include young people under 25 in different processes.

The inclusion of women presents a similar challenge. Women are not very present in public fora, and some women do not dare to speak in mixed groups. In certain localities, when they are at home, they require their husband to be present during interviews. It continues to be necessary, therefore, to implement specific initiatives exclusively for young women.

Permanent dialogue groups facilitate cross-border exchange

Recurring and deeply interconnected conflicts have claimed millions of lives and disrupted social cohesion in the Great Lakes region since the 1960s. Conflict dynamics on one side of a border often have an impact on the other, due to the interdependence between countries of the region.

For almost a decade, Interpeace’s engagement in the Great Lakes region focused on establishing GDPs to facilitate cross-border exchange. In these dialogue spaces, communities can openly discuss the root causes of conflicts and propose solutions to address them. GDPs have helped to develop consensus-based and locally owned solutions and have assisted decision-makers to connect with and consult local populations.

In 2021, the second phase of the Great Lakes cross-border dialogue programme came to an end. Building on the successes achieved in the region, Interpeace launched a new area of work, that focuses on the leadership roles of youth and women in mediation and peacebuilding processes.

Fostering youth leadership to build peace

Young people are the majority of the population in the Great Lakes countries and they are severely affected by its cycles of protracted conflict. They face physical violence, forced recruitment into armed groups, intergenerational transmission of trauma, and forced displacement, and have lost access to schooling, jobs and livelihood opportunities. Despite these challenges, previous and ongoing peacebuilding interventions have not offered young people sufficient space to enable them to participate meaningfully in dialogues and shared peacebuilding actions.

Through the new regional initiative launched in 2021, Interpeace is taking action to equip young people in Burundi, the DRC, Rwanda and Uganda with the skills and knowledge they need to influence and play a more effective leadership role in regional peace processes.

The Great Lakes Youth Innovation Lab for Peace (YouthLab) is an initiative implemented in partnership with Never Again Rwanda (NAR), the Pole Institute, and the Centre d’Alerte et Prevention des Conflits (CENAP) and the Refugee Law Project which joined the initiative in late 2021. The initiative is funded by the European Union and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

The project provides a platform for young people in the Great Lakes to participate in dialogues and take action together, as they engage policy makers and articulate their vision for peace in the region.

The project brings together young people in the region to participate in and lead initiatives that contribute to governance, peacebuilding, and development processes at local, national and regional level. It also supports youth leadership in peacebuilding and expands cultural and inter-generational exchanges.

The new project builds on the perceptions and lessons learned from earlier, extensive Interpeace research. The programme addresses positively the important national distinctions that exist in the region and that can contribute to overcoming misunderstanding, tension and conflict. The figures below illustrate these:

Great Lakes Youth Lab participants’ perceived capacity to influence decision-making

[ninja_charts id="14"] [ninja_charts id="15"] [ninja_charts id="16"]

For peace to be built, maintained and nurtured, it must be embedded in the behaviour towards citizens of formal institutions of the State, and become embedded in their way of governing. The creation of a sustainable national infrastructure for peace that allows societies and States to resolve conflicts internally, by applying their own skills, institutions and resources, is essential to building a culture of peace.

Peacebuilding must look beyond working with civil society and communities if it is to be lasting, have impact, and be anchored in engagement with authorities. Formal partnerships with State institutions are crucial to a successful Track 6 strategy and to peacebuilding that lives up to its own values and principles. Peacebuilding outcomes are not only achieved by peacebuilders; collaboration between sectors is essential. It ensures, for instance, that structural shifts across the ODA system inform how aid is planned and financed and whether aid can respond to the needs of the most vulnerable, including in conflict contexts. To achieve behavioural change and a cumulative impact on peace, it is essential to adopt collaborative approaches and focus on influencing the institutional requirements and incentives of relevant organizations. It is necessary to embed resilience oriented, participatory and local approaches in the actions and behaviour of development and humanitarian actors so that their actions more effectively contribute to peace.

Ultimately, Interpeace must ensure that its impact is designed to last beyond the organization’s involvement. In addition to embedding change in institutions, this requires that Interpeace’s strategies include self-sustaining business planning. By modelling this, Interpeace aims to influence how the wider peacebuilding, development and humanitarian sectors do their work.

7 country/regional programmes have partnerships with institutions responsible for promoting peace at national level, anchoring 20 advocacy initiatives launched in 2021 that aim to enhance State policies on peace and social cohesion.

14 recommendations made by Interpeace and its local partners have been adopted by State institutions in countries of intervention.

The Cross-Organizational Platform on Peace Responsiveness, convened by Interpeace, brings together Peace Responsiveness champions of seven UN Agencies (FAO, ILO, IOM, UNFPA, UNICEF, WFP and WHO).

Increasing women's representation and participation during Somaliland's parliamentary and local council elections

Democratisation continues to be an important pillar of efforts to sustain peace in the Somali region. Since the collapse of the government of Somalia in the early 1990s, the region has struggled to establish governance systems that foster citizen ownership of and participation in State-building processes. Given the importance of responsive, participatory, and inclusive governance to building and sustaining peace, creating platforms that facilitate citizen participation in decision-making is an essential element of work to consolidate peacebuilding gains.

As part of Interpeace's efforts to promote greater inclusion in State-building processes, the programme developed interventions that advocated for increased representation of women in Somaliland local council and parliamentary elections. Interpeace carried out this work in cooperation with its partners and Media INK. Media INK worked with NAGAAD to assist female candidates to enhance their communication skills and visibility to voters. NAGAAD promoted public discussion of women's participation and representation in politics. Its campaign challenged misconceptions in Somaliland about women’s roles in decision-making, and the marginalisation of women in politics. Other activities included social media coverage, communication support for selected female candidates, production and dissemination of radio programmes, and making promotional videos for female candidates. In total, 28 female candidates were selected to run by Somaliland’s three political parties. Although few women were elected, the level of support they attracted highlighted the importance of investing over the long term to make women electable, and able to challenge social norms that impede women's political representation and participation.

Mayan Sheikh Dahir Gelle, a 40-year-old old single mother of nine children, took part in the 2021 elections. When describing her motivation to run, she underlined that woman in her country are not well represented in legislative bodies and are culturally deprived of a voice in their society. “I ran for the elections because, as a female entrepreneur in Borama, I have seen and come across many issues faced by the women vendors in the local market, and I wanted to have a position in the local government in order to bring their attention to issues of women,” Maryan Sheikh said. “In Somaliland women are the backbone of the society and they put a lot of effort into the society’s development, but they are very rarely represented and heard in decision-making bodies of the country. My motivation was also to create a voice for women in Borama local government.” Maryan said that she was fortunate because her family, as well as sultans and elders of her community, supported her from the day she announced that she would be a candidate. “Many people in the community were supportive since they knew about me as an advocate for social change. The community people very much accepted that I was running for local government elections, and believed that women are good at solving issues,” she added.

Maryan also emphasised the challenges that women participants had to face during the election process. For instance, male candidates would sit with clan elders at night and discuss their agendas, whereas female candidates were unable to participate in such meetings. “The cost of the campaign was very high. I sold all my gold and one of my houses to take part in the elections. For me it was easy to talk to people and express my motives to them, but there were clan-based challenges which crippled us, since most of the society preferred to elect men.”

Mayran is hopeful about the future. She is motivated, strong, passionate and enthusiastic. “I will not stop my journey here. My plan is to run for the parliamentary elections. I hope I will win one day, and I will have the opportunity to be the voice of the voiceless and to be a role model for other women who are advocates for social change.”

Despite significant advances, various groups continue to be marginalised in Somaliland society, particularly women and minority clans. This calls for a rethink of current initiatives to strengthen inclusion, specifically to promote the participation and representation of women and minority clans. The results of the 2021 elections, in which no female candidate was elected to the House of Representatives, highlighted this challenge.

Increasing the participation of youth in decision-making in Guinea Bissau

In Guinea Bissau, youth are traditionally excluded from decision-making processes by both formal and traditional institutions. Public debates and national institutions tend to adopt a top-down approach to policy development that does not take into account their views and concerns. Creating opportunities for inclusive dialogue and establishing entry points for youth that enable them to take part in community and local processes is key both to removing barriers that exclude youth and to building sustainable peace.

Interpeace’s project uses inter-generational dialogues to strengthen the relationship between youth leaders and officials from regional and local institutions. The dialogues have helped participants to develop a shared vision of barriers to and opportunities for youth participation. Interpeace also supports young people to design and implement regional youth-led advocacy initiatives, which give youth practical opportunities to discuss topics that matter to them with decision-makers. The young people who participated in these reported that, as a result of the programme, they felt more confident in their ability to participate in decision-making, were more proactive in their communities, and had been recognised by the representatives they had met from formal and traditional institutions.

In addition, the programme strengthened the relationship between youth organizations and the National Institute of Youth (INJ). Efforts to bring the views of youth to decision-makers were better coordinated, and it became easier to discuss proposals to establish a national agenda for YPS and integrate it in the National Youth Policy. Interpeace, Voz di Paz, the UN Peacebuilding Fund Secretariat, and the INJ all participated in a nationwide dialogue process that identified and validated a set of youth priorities for peace and security. These have been presented to the State Secretary for Youth and Sports and have underpinned a debate on developing a YPS Agenda in the country, using participatory methodologies that embed youth perspectives.

The mid-term evaluation of the project showed that, while relations between youth leaders and traditional and local institutions became closer, political parties remain difficult for youth to reach. Engaging the youth wings of political parties would be key to creating a positive environment for youth participation before the elections of 2023/2024, and Interpeace is exploring this further.

Perceptions among young people of their level of access to institutions in Guinea Bissau |

Trust of young people in their ability to influence local decision-making in Guinea Bissau |

| [ninja_charts id="7"] | [ninja_charts id="8"] |

Fostering intergenerational consensus on the role of youth

Between March and June 2021, 394 people from different generations participated in a national dialogue to develop a shared vision of the challenges and opportunities generated by youth participation in local decision-making. The dialogues took place in 11 localities, in every region of the country, enabling youth leaders active at regional level to meet older representatives of key regional government institutions. Of the participants, 42% represented local authorities (sectoral officials, Plano delegates, delegates from the Regional Education Directorate) and traditional authorities, and 59% were youth under the age of 35, selected after mapping formal and informal youth-based organizations in the country.

The dialogue laid the foundation for a shared understanding of the needs of youth and obstacles to youth participation at local level. At the end of each dialogue session, the participants validated a document that set out the main priorities for enhancing youth engagement and inclusion in decision-making bodies and regional institutions. More than 150 local government officials, traditional leaders, officers from various branches of the Security and Defence Forces (SDF), and representatives of political parties were willing to take part in these dialogues with the younger generation. In all, the process generated 11 documents setting out the priorities for youth participation in different regions.

The inter-generational dialogues have helped to create a shared agenda for addressing the needs of youth and the obstacles to, and opportunities for, their participation in decision-making processes and institutions. Cooperation between different generations emerged as a key factor. On one side, participants recognised that “old generations must recognise that youth have capacities and they need to cede space to them. It’s not only when they need youth force that old generations must remember them,” said Amadú Djau, a participant in the Gabu Dialogue session. On the other, it is vital to build young people’s capacity: “It is fundamental for youth to build their capacity to participate and create a change in the paradigm, making old people trust in their new competencies and innovative capacities,” said Father Michael, a participant in the Quinhamel Dialogue Session.

Building trust between communities and police at the woreda level

Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa, and around 70% of its 120 million people are under the age of 29. When the Tigray war started in November 2020, Ethiopia’s political and security situation deteriorated. Security has improved since the beginning of 2022, and the government has created a National Dialogue Commission to create societal harmony and national consensus.

Interpeace has been working in Ethiopia since 2020 and has implemented projects in collaboration with the Ministry of Peace. Building trust between the local (woreda) police force and the communities they serve is one pillar of Interpeace’s work. Improving this relationship is critical in conflict-affected contexts. It reinforces a sense of citizenship and the overall social contract.

A new Police Doctrine was developed by the Ministry of Peace. The Doctrine sets the objective of “depoliticising, demilitarising, decentralising and democratising” the police and affirms the police service’s four values: police professionalism; respect for human rights; integrity; and respect for diversity. The police’s approach to building trust with citizens has four characteristics: openness, fairness, community involvement, and prevention. The Doctrine also describes a new approach to police accountability and oversight, making it clear that the police should operate only with public consent and that its performance should be measured in terms of public satisfaction and confidence (rather than in terms of crime levels and arrest rates).

Interpeace supported a nation-wide awareness effort by translating the Ethiopian Police Doctrine into five languages (Affan Oromo, Somali, Afar, Tigrigna, and English). The Ministry of Peace has distributed copies in all regions of the country. The programme supported senior government officials from all regions and city administrations to acquire a better understanding of the new Doctrine, as well as of the Independent Advisory Group and Neighbourhood Watch Groups that the doctrine promotes. The training helped to build national political understanding and support for the Doctrine.

To evaluate the progress that has been made in building local trust in the police, Interpeace conducted a baseline study in four woredas in Addis Ababa. In all, nearly 2,000 questionnaires were completed, as well as more than 80 interviews. The baseline study highlighted clear areas that can strengthen trust and collaboration between the public and the police, and the report will be an essential tool to promote a series of community-police dialogues in these woredas.

A community geographic information system (GIS) tool has been developed. This will help the police to adopt a collaborative, problem-solving and prevention-oriented approach in its relations with communities. The tool promotes interactive dialogue and collaboration between the police and communities at woreda level, and will assist the Independent Advisory Group to perform its accountability function and Neighbourhood Watch Groups to promote community security in collaboration with local police.

The escalation of violence in the second half of 2021 slowed Interpeace’s programme activities.

Perceptions of trust between communities and police

in four pilot woredas in Addis Ababa

The community supports and cooperates with the police as they go about their work |

I feel comfortable to go to police stations when I need policing services |

| [ninja_charts id="9"] | [ninja_charts id="10"] |

Where I have had contact with the police, I was satisfied with the way they deal with me |

The community in my area has high levels of trust in the police |

| [ninja_charts id="11"] | [ninja_charts id="12"] |

The police in my area do a good job |

||

| [ninja_charts id="13"] |

International aid in fragile and conflict-affected contexts can often be ineffective, rarely uses local potential to contribute proactively to peace, and sometimes even harms local peace and conflict dynamics. Although policy commitments urge all actors and sectors of the international system to do more and better to sustain peace, implementation remains sub-optimal.

The significance of Peace Responsiveness and

its impact on people’s lives

Interpeace’s Peace Responsiveness approach drives an ambitious agenda of change. It seeks to enable actors that operate in conflict-affected or fragile contexts to be more conflict-sensitive and more able to contribute deliberately to peace through their technical programming. Peace Responsiveness is an operational paradigm that enables actors that do not have peacebuilding at the core of their mandate to create opportunities purposefully for peace while achieving outcomes they set in accordance with their own mandates.

Ultimately, this programme seeks to make a difference by enabling the international system and all its components to address better the needs of people affected by crisis and conflict. It also seeks to create an international system that is fit for purpose, able to advance the Sustainable Development Goals.

Key achievements and the impact of Peace Responsiveness in 2021

Organizational level

In 2021, Interpeace strengthened and deepened its partnerships with WHO, UNFPA, ILO, FAO, and IOM. Considerable advances were made towards mainstreaming Peace Responsiveness within these organizations; gains were made both in terms of high level buy-in and broader institutional support for a peace responsive approach in these organizations’ policies and technical work.

Programmatic level

In 2021, Interpeace explored opportunities for joint programming with development, humanitarian and stabilisation actors at country level.

In Ukraine, Interpeace jointly developed a proposal for a peace and health programme with the WHO Country Office.

An exploratory phase for potential peace and health programming in the Mandera Triangle (straddling Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia) was concluded.

Individual level

The peace responsive approach recognises the roles that individuals play in influencing and shaping the overall architecture of organizations, the delivery of programmes, and the wider system.

In 2021, Interpeace held two editions of Effective Advising in Complex Contexts: Enabling Sustainable Peace. This course strengthens the capacity of participants to effect change in the contexts in which they work, and builds relevant skills.

Systems level

Peace Responsiveness is increasingly considered and recognised to be an operational approach and paradigm for advancing the HDP nexus and the Sustaining Peace Agenda. For instance, a variety of UN guidance and training tools now make reference to Peace Responsiveness.

In 2021, Interpeace made efforts to bring Peace Responsiveness into new policy forums, and to trigger conversations at strategic levels in the UN system and beyond. Through its engagement with Results Group 4 of the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) on Humanitarian and Development Collaboration, Interpeace was able to raise the profile of the peace element of the nexus in a forum that convenes humanitarian and development actors from across the system.

In addition, potential avenues for collaboration with numerous actors were explored, including with the Global Protection Cluster, the EU Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO), the Lives in Dignity Grant Facility, the Norwegian Refugee Council, the NYU Center on International Cooperation, and the Quaker United Nations Office in New York, among others.

Strengthening the links between peacebuilding and humanitarian aid at EU level

Interpeace staff also met with EU officials to advance Peace Responsiveness, including a high-level exchange leading to Interpeace’s participation in the 2022 European Humanitarian Forum.

Systemic change takes time and requires long term commitment

The changes that the Peace Responsiveness programme seeks touch on ingrained organizational cultures and wider structural dynamics. The nature of large multi-layered organizations also impedes the speed at which change can be achieved.

Peace Responsiveness requires a multidimensional approach, in which actors collaborate on a complementary basis to achieve collective impact. To improve coherence and increase synergy, Interpeace intends to continue beyond 2021 to support organizations to bridge their disciplinary siloes, as well as facilitate partnerships with organizations from other disciplines that have complementary expertise.

In line with its aim to secure systemic change as well as individual organizational improvement, Interpeace continued to convene in 2021 a Cross-Organizational Platform on Peace Responsiveness. The platform brings together champions of Peace Responsiveness from seven UN agencies, to discuss opportunities to operationalise and institutionalise the Sustaining Peace Agenda and the HDP nexus, as well as challenges to reaching those goals.

In global consultations for the ‘Independent Progress Study on Youth, Peace and Security (YPS): The Missing Peace’, a report commissioned by the UN, young women and men described their experience of marginalisation. They said they felt excluded politically, economically, educationally, and in relation to gender, and spoke of the “violence of exclusion”. In addition, although only a sliver of the youth population becomes involved in violence, youth are widely treated by their governments – and often their communities – as a threat, a source of risk, or a “problem to be solved”.

The resulting stereotypes and stigmas can create in some cases a “policy panic” that shapes the way young men and women are viewed, and generates counter-productive strategies that “securitise” young men and women, increasing their alienation and aggravating the mistrust that young people have in their governments, the multilateral system, and political systems and economies that have failed to serve them.

This experiential analysis lies at the heart of the global policy agenda on YPS, framed by UN Security Council Resolutions 2250, 2419 and 2535. The policy agenda affirms that it is essential to invest in the positive contributions of young women and men to building peace.

A youth-centred approach to building peace

The need for change also resonates with Interpeace’s commitment in its Strategy to invest in transformative resilience, including of young women and men – in their voices, agency, and leadership. Interpeace recognises the difference between “working with young people” and developing self-conscious, youth-centred approaches to building peace.

A core dimension of Interpeace’s work in 2021 was supporting country teams to develop, implement, and evaluate YPS country-level programming, in order to ensure that policy guidance will have a positive impact and help to reduce violence, thereby improving the safety and security of young people and the communities in which they live. This was taken forward practically by Interpeace programmes in Guinea Bissau, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Kenya, Ukraine, Rwanda, and the Great Lakes region. In addition, Interpeace worked to communicate the results of country programming to global policymakers, including at the United Nations, in order to influence global policy and decision-making.

In an example of a more direct opportunity for young people to engage with and influence decision-making on peace and security issues, Interpeace organized three seminars in the YPS Leadership Series in partnership with the University of Ulster, the John and Pat Hume Foundation, and the International Fund for Ireland. The audience was primarily youth peacebuilders in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The design of these events helped to kickstart a dialogue process among Northern Irish youth groups that led them to work more closely together and consider the benefits of a YPS framework for peacebuilding in the Northern Irish context.

Outside the box