Track 6: a strategy for inclusive peacebuilding

Violent conflict can arise from a wide variety of socio-political problems, and to build sustainable peace it is essential that all levels of a society come together in resolving them. Unfortunately however, protracted conflicts, violence, marginalization and exclusion all erode bonds of trust and deepen social divisions, meaning that very often, local communities, civil society and political elites seek to address these challenges independently of each other. External actors too can only foster real change if their work is rooted in local realities and underpinned by trust within a given society. Because of this, strengthening the links between the different levels of society should be the foremost priority for peacebuilding.

Interpeace has learned this lesson first-hand, through more than 22 years of work in conflict-affected regions around the world. Interpeace seeks to facilitate positive interactions between three levels, or “tracks” of society, by strengthening lines of communication and building trust, and providing spaces for dialogue where previously these may have been weak or completely absent.

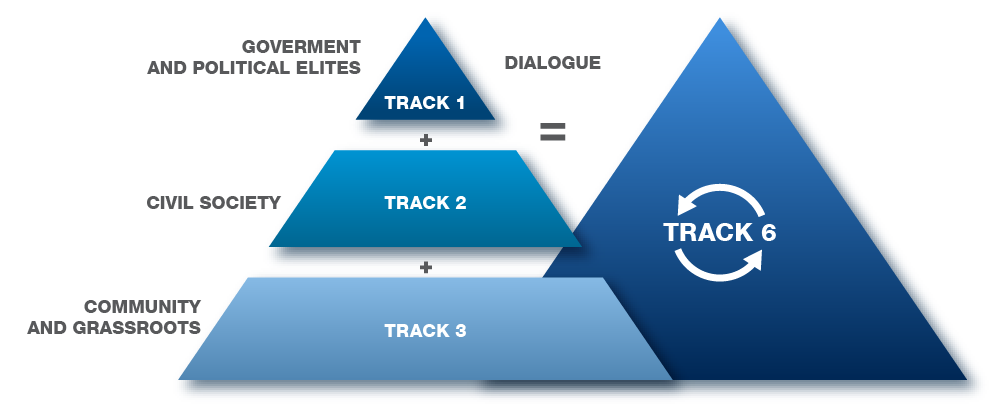

The three “tracks” are broadly differentiated by levels of influence and formal organisation, and can be summarised as follows:

Track 1: Political elites and decision-makers both at the national and international levels

Track 2: Civil society and local government, influencers, think tanks, private sector and researchers

Track 3: Local communities and individuals within the broader population

An enormous amount of work has been done at each of these different levels, but the focus is rarely on the links between them. Consequently, solutions are disconnected or only owned by one part of society – and are thus rarely sustainable. Connecting the “tracks” can help societies move towards a situation in which high-level policies are informed by the knowledge and experience of local communities and civil society, and which therefore reflect local realities. Additionally, local communities and civil society are likely to have a better understanding of the way high-level policies are conceived. This is the essence of the “Track 6” approach: 1 + 2 + 3 = 6.

Interpeace’s mandate has two core pillars. The first is strengthening the capacities of societies to manage conflict in non-violent, non-coercive ways by assisting national actors in their efforts to develop social and political cohesion. The second involves assisting policy-makers at the national and international levels to play a more effective role in supporting peacebuilding efforts around the world. The Track 6 approach helps us bring those pillars together, ensuring that lessons learned in the field are understood and applied, to continue the evolution and improvement of peacebuilding practice.

Developing an inclusive approach to peacebuilding

There have been many instances in the past where international and national policies intended to resolve conflict[1] were designed without the ownership of those that the policies would affect most. As a result, these policies often failed or had limited impact. At the same time, grassroots communities and civil society organisations may have a limited understanding of the impacts of wider political dynamics on their lives– and have limited avenues to influencing political elites. Recognising this, Interpeace developed Track 6 as a strategic approach to inclusive peacebuilding. The following section describes the different ways this approach is manifested through Interpeace’s programmes.

Somali Region. Photo credit: CRD

Mali: a nation-wide dialogue

In Mali, the Track 6 approach has been key to building the legitimacy and credibility of the programme from the local to the national level. Since its inception, the emphasis has been on ensuring a broad and inclusive national process that involves all regions of the country and cuts across all levels of society. Using such an approach can help to both ensure transparency and accountability in national governance, and reinforce the capacities of Malians to resolve their conflicts peacefully through greater agency and stronger relationships of trust. The first phase of the programme involved organising a nation-wide dialogue – based on the principles of inclusivity – with the goal of developing a shared understanding of national peacebuilding priorities. The results of the dialogue highlighted the urgent need to enhance trust between citizens and the Malian authorities.

Building on this national dialogue, Interpeace and its local partner, the Malian Institute of Research and Action for Peace (IMRAP), conducted a participatory action-research process to develop a shared vision of possible solutions to this breakdown of trust. The process engaged more than 2000 Malians across the three “tracks” – throughout the country and in neighbouring refugee camps – and led to the publication of two reports and documentary films.

The implementation process of these solutions led to a unique engagement of the Track 1 actors, namely the Government of Mali, and in particular the Malian Defence and Security Forces (DSF). Bringing the results of the research to high level decision makers and lower-ranking elements of the DSF helped reach out to the civil society and local communities, which created the conditions that enabled rebuilding relationships of trust between the DSF and the wider Malian population.

To complement this work, the programme engaged Security Sector Reform (SSR) officials in the establishment of permanent spaces for dialogue between the Malian population (Track 3), civil society (Track 2) and key people in the security field (Track 1). The intention is that these dialogue spaces would evolve into Local Security Consultative Committees (CCL); an institution whose creation is foreseen by the peace agreement.

Mali. Photo credit: Interpeace

El Salvador: empowering local actors in the process of social change

Processes of social transformation are not linear and require a deep understanding of the social and political context to identify the right moments and opportunities for encouraging change. Empowering local communities to participate in the process increases the likelihood that top-down policies will meet the changing needs of the public, thereby increasing their legitimacy and sustainability.

In El Salvador, violence is the most visible expression of social exclusion, institutional fragility and a lack of educational and economic opportunities. In March 2012, a truce between El Salvador’s main gangs contributed to a 60% decline in homicide rates, demonstrating the existence of alternatives for violence reduction. However, when the truce broke down in November 2015, homicides rates reached their highest levels in decades.

To achieve a sustained reduction in violence and insecurity, Interpeace initiated a broader process of non-violent conflict transformation that sought to empower local actors using the Track 6 approach.

Lacking economic opportunities, vulnerable youths frequently turn to illegal economy which are normally fuelled by criminal activities and violence. Consequently, a key long-term strategy for Interpeace has been working at the Track 3 level (grassroots) on the development of youth entrepreneurship opportunities as an alternative to illegal economy. This strategy seeks to provide youth at risk with technical training that will enable them to join the labour market and create their own businesses. To achieve this, Interpeace consulted with 216 young people in 61 communities, which established the training needs and opportunities for entrepreneurship in different municipalities. Participants then took part in workshops to strengthen their skills in violence prevention, peace culture, re-integration and rehabilitation, and went on to receive further training sessions on entrepreneurship to meet the needs and opportunities established in the surveys. This work is now underway in five different municipalities of El Salvador.

Engaging in issues of entrepreneurship offers the chance to improve social cohesion and promote inclusion by providing at-risk youth with a sense of identity, solidarity, confidence and the opportunity to develop the same values that could attract them to gangs in the first place, but in non-violent and non-criminal ways.

At the Track 2 level, Interpeace works with 10 municipalities across El Salvador to consolidate the successful development of youth entrepreneurship as an alternative to illegal economy. Letters of understanding have now been signed between the municipalities to ensure an inclusive collaboration. This collaboration also contributes to Interpeace’s objective of strengthening the legitimacy of public institutions when it comes to violence prevention. Meanwhile, work at the Track 1 level has focused on a programme of training and dialogue with El Salvador’s National Police, which is strengthening their capacity to transform violent conflict in non-violent ways, improve prevention methods and reduce exclusion by limiting the use of violent repression. The Ministries of Interior and Territorial Development, Justice and Public Security, Agriculture and Livestock, and Labor and Social Welfare, have also been directly involved with Interpeace’s project.

El Salvador. Photo credit: Interpeace

The Somali Region: “Compressing the vertical gap” between decision-makers and grassroots

Much peacebuilding work in the past has typically focused on either working with high-level decision-makers to help them better understand the needs of local communities, or working with those communities to better understand political elites. While building this understanding is important, it is equally important to work between these tracks, engaging with people across the vertical axis of society. Involving everyone helps establish trust through collective identification of issues and solutions, and joint implementation of consensual, peaceful social transformations.

Over the course of two decades working in the Somali Region, Interpeace and its partner organizations have supported and advanced state-building and peacebuilding processes. Our work has helped transform dialogue into action in the interest of communities across the region, by convening a wide range of stakeholders in neutral political spaces, using the Track 6 approach. Working through long-term institutional partners the Academy for Peace and Development (APD) in Somaliland and the Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) in Puntland has ensured local ownership of the peacebuilding approach.

The Interpeace Pillars of Peace programme concluded in 2016, although its Democratization element continues with ongoing support to the Voter Registration process in Somaliland. The Pillars of Peace Programme was established in 2009 with the objective of building social cohesion, aimed at strengthening the capacities of communities at the Track 3 levels to connect with and influence evolving Track 1 governance structures. The Democratization Programme, initiated in 2005 with the Somaliland Parliamentary elections, has run continuously until today in both Somaliland and Puntland. It was born out of the Dialogue for Peace Programme, following the recognition by Somaliland stakeholders of the importance of the parliamentary elections to peace, and focusing on electoral democratic processes aimed at strengthening democratic institutions and increasing public trust. Together, these programmes played a major role in bridging local communities and leaders at multiple levels, thereby “compressing the vertical space” and laying the lines for long-term communication.

As the technical lead supporting the Somaliland National Electoral Commission (NEC), Interpeace used the Track 6 approach to contribute to the increased legitimacy of the democratization and electoral processes, using participatory processes in its support to the NEC. This ensured that the political elite were engaged with civil society actors, and that the population was accessed and engaged to ensure levels of accountability of the NEC throughout recently completed Biometric Voter Registration process. For example, the NEC consulted regional universities and local stakeholders in the selection and recruitment of field staff, and the voter registration system was extensively tested with and demonstrated to key stakeholders in the process, including the public and civil society organisations such as APD, to collect feedback, make adjustments, and most importantly, ensure buy-in across all three tracks. Beyond using participatory processes to inform technical decisions, the Track 6 approach was also used in related efforts such as voter education. This was a collaborative process that went through the NEC (Track 1), from CSOs that were implementing voter education (Track 2) for a coordinated effort to raise awareness of the populace (Track 3) on the importance of the voter registration process and how to register. A key strategy in the democratisation process has also been to strengthen the links by working from the middle - the media (track 2) – to affect both the political elite and citizens through development of media codes of conduct for sensitive processes such as the voter registration.

Somali Region. Photo credit: PDRC

Côte d’Ivoire: linking findings on the ground to more effective policy reform

In the aftermath of the Ivorian socio-political crisis that officially ended in 2011, a violent phenomenon that began in the Attécoubé commune in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, has spread to neighbouring districts. Young men between the ages of 12 and 27 join organized youth groups, known as “microbes”, who engage in extremely violent acts, both to make ends meet and with the aim of “becoming someone”. Seeing this phenomenon first and foremost as a security problem, the government of Côte d’Ivoire has attempted to tackle it, at times vigorously using force to arrest them. Conscious of the vicious cycle a security response can create in this context, Interpeace and its partner Indigo Côte d’Ivoire are working to both reintegrate these youths and strengthen the capacities of Ivorians to reduce and overcome violence, as well as to support the development of more effective policies to better resolve and prevent this form of urban violence.

The Track 6 approach has been crucial for bringing about social change in Côte d’Ivoire, with the programme engaging at-risk youths as well as their families and communities (Track 3), the private sector and civil society (Track 2), as well as state institutions, influential elites and politicians (Track 1). Over the course of 9 months in Abobo – one of the poorest and most conflict-affected communes in Abidjan, Interpeace and Indigo, with support from UNICEF, conducted a pilot project aimed at socially and economically reintegrating the vulnerable youth known as “microbes”. The project engaged youths’ families, communities, authorities and the private sector using dialogue as a tool for social transformation. The project’s primary objectives were to better understand the “microbes” phenomenon and test alternative approaches to draw technical recommendations, lessons learned and best practice. While these were achieved, the project ultimately also led to the socio-economic reintegration of 40 young men and teenagers. A key success factor of the project was the involvement of all sectors of society – from the parents, community to the private sector, whose engagement, coupled with a special attention geared towards social recognition, helped adequate at-risk youths divert from violence.

While the work described above was undertaken in pursuit of the first part of Interpeace’s mandate, the findings and outcomes of our engagement in Abidjan since 2014 increased our capacity to influence policy and processes around urban violence at the Track 1 level. Our findings and recommendations informed among others the Ministry of Youth and Youth Employment and Civic Service in the development of its National Youth Policy, and the Ministry of Solidarity and Social Cohesion with its strategic plan. Furthermore, the programme accompanied the National Security Council in the process of establishing resocialization centers for–the so-called “microbes” – an achievement for both the Government of Côte d’Ivoire and Interpeace’s work to influence policy.

Côte d'Ivoire. Photo credit: INDIGO

Cyprus: inclusive multi-stakeholder dialogue processes to safeguard sustainable peace

By building on grassroots consultations, informed participatory research processes and inclusive dialogue spaces, the Track 6 approach helps foster both vertical and horizontal links. In Cyprus, Interpeace has focused on connecting Track 1 level negotiations with civil society (Track 2) and the wider population (Track 3), to help work towards the island’s reunification. This has been done in partnership with the Centre for Sustainable Peace and Democratic Development (SeeD), the country's first bi-communal think tank. The joint programme has developed an innovative tool and fostered evidence-based dialogue and policy-making through Participatory Polling and the use of the Social Cohesion and Reconciliation (SCORE) Index.

At first, negotiation processes were focused solely on the Track 1 level, with limited consensual sourcing of information on public perceptions. Through the implementation of participatory polling, the programme has helped provide information on the public perceptions of the Cyprus Peace Talks. Collecting this information simultaneously from both communities (Track 3) in an impartial and confidential way, and making it available to the negotiating parties, technical committees and UN officials (Track 1), has helped fill a significant knowledge gap that may otherwise prove to be a significant obstacle to reaching an agreement.

Although considerable progress has been achieved in the Cyprus Peace Process, negotiations around a contentious “security dossier” is still locked in a zero-sum dynamic, where one side’s gain is the other’s loss. For this reason, in October 2016, SeeD launched the “Security Dialogue Initiative” with its international partners, Interpeace and the Berghof Foundation. The project has sought to find innovative solutions to overcome the deadlock on security, so that solutions can be found that make both the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities feel simultaneously and equally secure. The first phase of the research employed qualitative methods that included 20 thematic focus groups with the local populations (Track 3), over 50 interviews with policy makers and elites, and open dialogue and consultation with local and international security experts (Track 2 and Track 1). The second phase included a quantitative opinion poll based on a representative random sample of 3000 people, 1500 from each community (Track 3), as well as expert vetting of the security proposal by Cypriot, Turkish, Greek and other international security specialists (Track 1). Making the results of the participatory polls available to negotiators, technical committees, the UN Good Offices and, when appropriate the general public, will fill a critical gap that may otherwise prove to be a significant obstacle to reaching an agreement acceptable to the two Cypriot communities.

Cyprus. Photo credit: SEED

Colombia: transforming public institutions through a Track 6 approach

In the same way that societies are comprised of different sectors, so too are public institutions. Because of this, the methods used at a national scale can be used to help transform the capacities and legitimacy of public institutions.

The signing of the peace agreement in Colombia put an end to 52 years of armed conflict and marked the beginning of a process to build lasting and sustainable peace. Although the plebiscite to ratify the agreement narrowly failed on October 2nd, 2016, a new agreement, which was ratified by Congress, was reached on November 24. The National Police of Colombia is a key institution in the peacebuilding process, because of its role in guaranteeing security, furthering peaceful coexistence and preventing violence. Interpeace believes that supporting public institutions and existing civil society efforts towards peace will increase social and institutional capacities to transform conflicts non-violently. Therefore, in partnership with Alianza para la Paz, the programme is working with the National Police of Colombia to incorporate a peacebuilding approach and ensure that the institution remains trusted and legitimate against the post-conflict challenges and the emergence of new forms of armed violence.

The National Police of Colombia is hierarchical, and because of this is clearly divided into different sectors. This separation puts a certain distance between sectors and how they view and experience conflict in their daily work. As a result, Interpeace applies the Track 6 approach as a way of better integrating sectors within the institution to help guarantee the sustainability and legitimacy of the Strategic Transition Path for the National Police of Colombia. Through a participatory research process, Interpeace engaged with more than 125,000 police officers (Track 3) in a survey to determine their perceptions of the current peace process and their aspirations to the role they can play in the implementation of the peace agreement. This survey provided unique insights that allowed better-informed decision making in the Track 1 leadership of the institution.

The programme also engaged with more than 400 police officers in the technical and intellectual sectors of the institution (Track 2), to determine the strategic orientations that the police should implement in order to consolidate their post-conflict responsibilities. As a result, of this internal inclusive dialogue process, six strategic lines were defined, which served as the basis for the development of the “Peacebuilding Model of the National Police”, which will be led by decision-making officials (Track 1). This model includes an implementation plan for the short, medium and long term.

Colombia. Photo credit: MEBOG - COEST

Frameworks for Assessing Resilience (FAR): generating an evidence base for prevention

Engaging with all sectors of society – be it women, the youth, the elderly, indigenous populations, politicians or businesspeople – and enabling them to communicate in a safe environment, generates invaluable knowledge. This inclusivity validates the knowledge and can help identify problems and solutions with more certainty – a first step towards positive social change.

Through the two-year Frameworks for Assessing Resilience (FAR) programme, launched in 2014 and designed by Interpeace with funding from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA), Interpeace has made significant progress in identifying, analyzing and strengthening sources of resilience for peace. Conflict prevention work has typically focused on top-down fragility assessments and conflict analysis undertaken by external actors. While these methods are of fundamental importance, Interpeace believes that in order to transform conflict, it is not only necessary to identify its causes, but also to understand the existing capacities of societies to resolve problems non-violently. Through qualitative consultations, as well as quantitative surveys and multi-sector dialogue processes, the Track 6 approach was applied to three countries - Liberia, Guatemala and Timor-Leste – seeking to propose national-level recommendations for overcoming the most pressing impediments to peace. The first phase of the project was a national consultation process, bringing together Track 3 grassroots communities to identify the main sources of conflict and how people address them. Based on these findings, a participatory action-research was undertaken with a wide range of members from Track 2 civil society, to develop proposals which were then presented to Track 1 national authorities and in relevant international fora.

A guidance note has now been developed, capturing the analytical and operational lessons learnt during the two-year programme. This document fills a critical gap in the literature and practice of resilience, which has mostly focused on resilience to humanitarian crisis and disaster without paying attention to the specificities of resilience to violent conflict. Interpeace is now working to sensitize peacebuilding practitioners and policy-makers to the potential of resilience-based approaches, one early outcome of which has been helping to inform the EU on how to integrate resilience to violent conflict into its broader resilience strategies.

Timor-Leste. Photo credit: Steve Tickner

Conclusion: ensuring inclusion and cohesion from bottom to top

By ensuring the meaningful participation of people from all sectors of society and institutions, through strategies and mechanisms that are adapted to each context, the Track 6 approach helps foster inclusive political processes, that will guarantee trust and legitimacy. Our experience shows that the best and most lasting solutions to conflict are those that are coherent from bottom to top, broadly owned, and ultimately more legitimate. Through participatory action-research and multi-stakeholder dialogue, direct programming and policy recommendations, Interpeace is able to formulate more effective peacebuilding initiatives at the local, national and international levels.

[1] At Interpeace we believe that conflict is natural to society and it can be a source of positive change when it is addressed through non-violent means. Therefore, conflict is not something to be resolved, but transformed, based on the endogenous capacities for peace that are found in each society.